The author found himself interning at Electronic Arts for 10 weeks one summer, thanks to a fateful TED-like video and a LinkedIn suggestion. (Source: nickstone333 on Flickr. Some rights reserved.)

Editor’s note on the term “internship”: Doctoral students in clinical, counseling, and school psychology may hear “internship” referenced in this post and immediately think of the yearlong field placement in a therapeutic setting that is required just prior to earning the doctorate. Here, author Stephen Gray refers to a different kind of internship–one that may interest students in science and research fields who are considering non-academic experience prior to graduation.

A leg up

Internship. It may be a strange word to weathered doctoral students who have done nothing but tirelessly toil away on research studies for years, but in a world where there are an increasing number of PhDs and a decreasing number of tenure track jobs, it may become something to consider as the job market continues to shift. And while the term may invoke images of demoralized undergraduates getting coffee for high level CEOs, rest assured that there are plenty of companies and organizations interested in taking advantage of the unique skills a graduate student in psychology has to offer.

Although giving up a summer of research may slightly delay the timing of your degree, an internship offers invaluable experience in knowing what research in the “real world” is like and may allow you to determine if it’s a good fit for you. Having an internship on the resume gives you a leg up compared to other industry-bound students when applying for jobs, and in some cases, may even result in a permanent job offer from the company at which you intern.

Finding my way into an internship

To be completely honest, I didn’t come into the summer before my fifth year as a doctoral student with intention of finding an internship – things just sort of worked out that way.

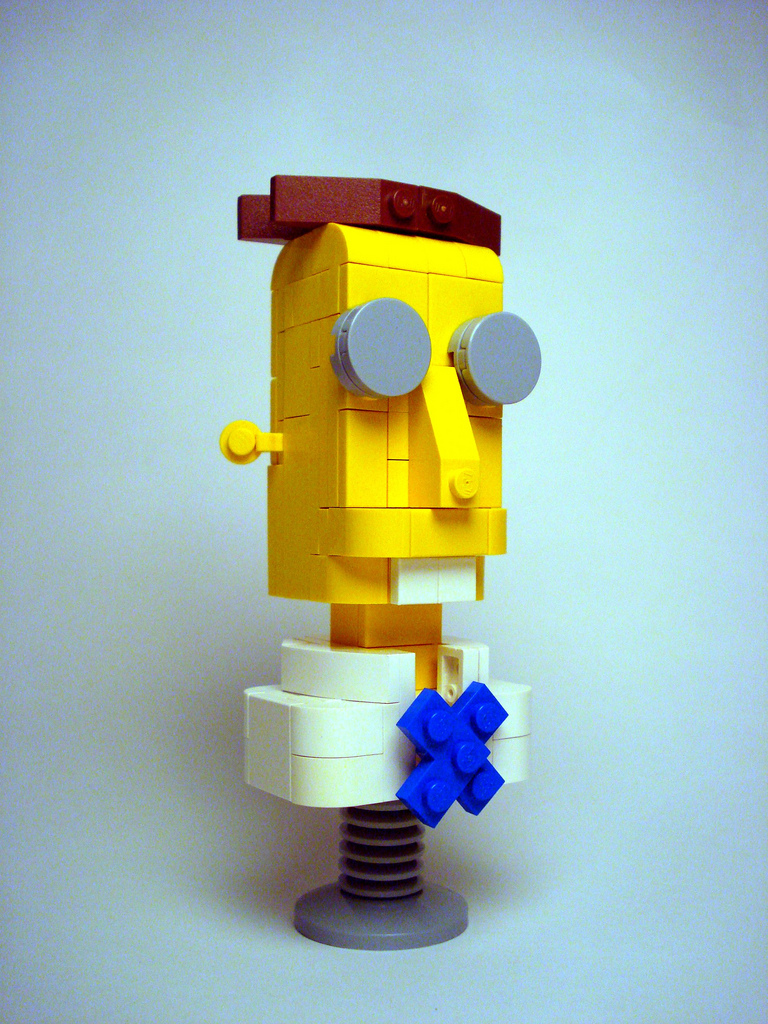

It started a few years ago, when I stumbled upon a TED-style online talk by Dr. Jeffrey Lin, the head of social systems at Riot Games. Dr. Lin, who has a PhD in cognitive neuroscience from the University of Washington, spoke of the research Riot Games was conducting to reduce negative player behavior in the game League of Legends. As a passionate online gamer myself, the idea that I could use my skills as a researcher to study how people interact with video games was enticing.

Per Dr. Lin’s recommendation, I joined a LinkedIn group called “Games User Research,” and came in contact with dozens of individuals with psychology degrees who were now using their skills for the gaming industry. Desperate to get some hands-on experience myself, I made a post introducing myself and asking about opportunities for freelance work.

To my surprise, I received quite a few responses, although the one that stood out to me was a Consumer Insights internship at Electronic Arts (EA) in which I would be working for an individual with a PhD in social psychology. After submitting my application and a series of interviews, I was soon headed to Los Angeles to begin my summer as a researcher at EA.

My favorite part of industry research is its blistering pace…I was also fortunate to receive a hiring recommendation

Turning an internship into a potential job

The experience I gained was invaluable. My favorite part of industry research is its blistering pace; I was able to dabble in six different projects while I was at EA in ten short weeks. I conducted literature searches, analyzed large sets of survey data, and presented my results to stakeholders and executives. I was also fortunate to receive a hiring recommendation, meaning that I have a potential job waiting for me when I finish my PhD next year.

The industry world is not for everyone – there are plenty of students (and advisors) who scoff at the idea of doing anything but academic research, and that’s okay. For the rest of you who are on the fence about what to do with your degree, I would highly recommend seeking out an internship that fits your passion. Even you dislike the experience, it will provide critical information about the right career path for you.

Editor’s note: Stephen Gray is a PhD student in experimental psychology, focusing on cognitive neuroscience, at the University of Chicago. Stephen is completing a two-year term on the APAGS Science Committee.